PHRs: what problem are we trying to solve?

PHRs: what problem are we trying to solve?

Robert Rowley, MD, Healthcare and health IT consultant, practicing family physician

Twitter: @RRowleyMD

“Patient engagement” is one of the buzzwords in health policy these days, and substantial data exist to show that when patients are actively engaged with the health care system, particularly if they have a chronic medical condition, their resulting health outcomes are better.

Clearly, it’s a good thing for people to be involved in their own care, and have the tools to do that. But how pivotal is this to lowering the health care cost burden that plagues the U.S. healthcare system? With better tools and higher engagement than what we have now, the impact will likely be significant.

The U.S. spends nearly twice what other developed industrialized counties do on health care, without evidence that such spending results in measurably better outcomes. And who uses these services? A recent statistic I saw in a presentation by a major health plan showed that, in any given year, about 5% of the population consume about 50% of the health care services.

The problem is that this 5% is not a homogeneous group – it is “lumpy.” About half of such high utilizing patients have chronic disease, and are members of the 5% year after year – well-coordinated case management can be very effective here.

The others, though, are people who develop a major condition one year, but were not in the 5% the year before (or any year, for that matter) – people who develop breast cancer, or have a heart attack, or break a hip. Considerable effort has been spent on creating “predictive modeling” risk-assessment tools to identify who might end up in “next year’s 5%,” and do something now to ward off the catastrophic event before it happens. Active participation by such at-risk individuals, once they have been identified, is important if such preventive efforts are to be effective.

Consumers vs. patients

This may be splitting hairs, but we might want to make a distinction between consumers and patients. This has some relevance when looking at Internet tools that can be built.

Eventually, all consumers become patients (or, almost everyone). However, the term “patient” comes into play when someone (a consumer) engages the health care system. It is the relationship with a healthcare provider (doctor, hospital, pharmacy, home health nurse, dentist, etc.) that defines a consumer as a “patient.”

[Read Related Article: Feds Raising Awareness of Patient Rights on Accessing Health Data]

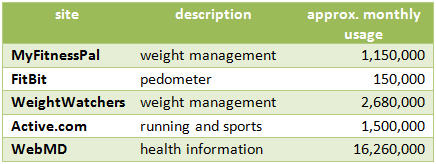

When it comes to the Internet, consumers (even around health issues) and patients have quite different levels of engagement. If one uses an external web site traffic monitoring tool like Quantcast, and one searches for traffic levels of various consumer health sites, one can see engagement in the millions, even tens of millions of users:

Patient-centered Internet sites are fewer, so are harder to compare, since most of them are portals that are pushed out to patients by their healthcare providers (the Personal Health Record systems – PHRs – that we are familiar with today), and therefore are not accessible by the general public.

So what can be understood by this?

Web portals that connect consumers as patients with their providers have dramatically less traction than consumer-centered health portals. Consumer-based products are self-service, self-sign-on, and are driven by a prior interest in their service – people wanting to manage their weight, their fitness, their health activities. Further, the success of consumer Internet products is driven largely by their ability to share one’s successes with circles of friends – a support group or network. Facebook applications as elements of such services enhance this even further. It is precisely the sharing of one’s success that drives the high levels of engagement seen in these consumer Internet products.

Building patient engagement

There is much we can learn from the experience of consumer Internet health sites that can be applied to a new generation of patient-facing products.

A PHR needs to be thought of as a patient engagement tool. The kinds of consumer engagement seen with Internet sites, as noted above, needs to be harnessed if there is to be a true shift in the culture of healthcare in this country, and individuals are truly empowered and engaged in their care. Such tools can potentially offer better transparency around cost and quality for services they may need, and avoidable things (like avoidable re-admissions to hospitals within 30 days after discharge) can be reduced considerably. Prompting for when wellness (or chronic disease management) things need to be done can flow through such products.

As we stand on the threshold of building the next generation of PHRs, moving beyond the current generation of EHR-connected portals and towards an independent PHR that can connect with any/all doctor EHRs, there are lessons that can be learned from the consumer Internet:

- There needs to be self-sign-up. Within the PHR, there needs to be a collection of sufficiently valuable tools that consumers will want to sign up on their own, even if not connected anywhere.

- There needs to be a very easy way of connecting with one’s physician’s EHR (if they have one – and the majority of physicians now do). It needs to be simple, clear and automated, taking lessons from tools like Quicken, or TurboTax, or Mint.com – all the jargon needs to be stripped from the process.

- The data that is gleaned from EHR connection needs to be displayed in easy terms, with graphs that are compelling.

- There needs to be a way of socially sharing one’s successes (selectively) with circles of friends. A Facebook app has utility here.

- Once a connection is made with one’s doctor’s EHR, then two-way communication needs to be enabled. One must be able to ask questions, get interpretation of one’s lab results, request refills, make or request appointments, etc.

- One must be able to not only see one’s medications, allergies, immunizations, problem lists (in plain English), but be able to download them into your PHR so that it is portable, can be printed if desired, or uploaded to a different doctor’s system (like when one changes insurance, or health providers, or sees multiple doctors who each may be on different systems). For healthcare providers, this is important, since Stage 2 of Meaningful Use requires that at least 5% of one’s patients “download/print/transmit” their health information.

So, getting back to the original question – what problem is a PHR trying to solve – the answer is this: patient engagement is an important element of improving the quality and reducing the cost of health care in the U.S. It is urgent that this be done, as health care in this country is facing a crisis of affordability. Patient engagement is key. A PHR is a patient engagement tool.

Lessons can be gleaned from experience in consumer Internet health sites, and these lessons can be applied to the necessary next generation of PHRs – ones that are free-standing, can be signed up for by the consumer on her/his own, yet can be connected to any/all EHRs and act like the tethered portals we have become familiar with (but which have very low engagement at present).

This promises to be an exciting area of innovation. The entrepreneurial community is making runs at this vision from many different starting points, and creating elements of what will be a new type of platform for health, engaging us all as consumers become patients.

Robert Rowley is a practicing family physician and healthcare information technology consultant. From its inception through 2012, Dr. Rowley had been Practice Fusion’s Chief Medical Officer, having created the underlying technology in his own practice, and using that as the original foundation of the Practice Fusion web-based EHR. This article was first published on Dr. Rowley’s web site www.robertrowleymd.com.