Abundant Talent, Resources, Innovation — But Poorer Health Outcomes

Abundant Talent, Resources, Innovation — But Poorer Health Outcomes

By Gil Bashe, editor-in-chief , Medika Life

LinkedIn: Gil Bashe

X: @Gil_Bashe

Host of Health UnaBASHEd – #HealthUnaBASHEd

In a Fragmented System with Abundance — What’s Missing is an Aligned Priority

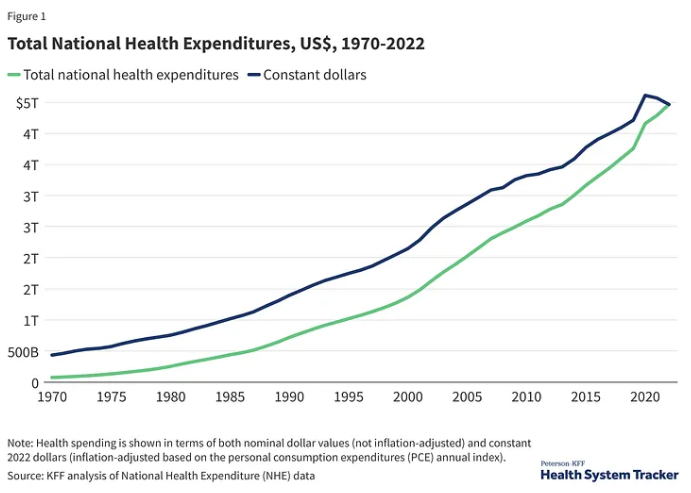

The United States leads the world in medical talent, resources and innovation. Physicians, nurses, pharmacists, technicians, and administrators are among the most highly trained globally. The nation spends nearly 18% of GDP — approximately $4.5 trillion annually — on health. American science drives global breakthroughs, from CAR-T therapies for cancer to life-saving cardiac devices and AI-driven diagnostics that are reshaping early detection.

Yet despite this abundance, Americans live shorter lives than people in other developed nations — by as much as 10 years, according to OECD data. Despite being first in spending, the Commonwealth Fund’s 2024 report ranks the U.S. last among 11 high-income nations for access, equity, and health outcomes. Millions still lack basic access to primary care, telehealth, and mental health services.

This is not a crisis of scarcity. It is a crisis of priorities. The U.S. health system does not consistently organize its clinical, financial, or policy decisions around the shared goal of improving people’s health: their physical and mental well-being.

Health economist Jane Sarasohn-Kahn has long argued that trust and continuity are as critical as any clinical intervention: when people feel unseen by the system, they disengage. She notes, “If the system doesn’t act as if it knows you, you will stop acting like you know the system.”

Note: Health spending is shown in nominal dollar values (not inflation-adjusted) and constant 2022 dollars (inflation-adjusted based on the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) annual index). Source: KFF analysis of National Health Expenditure

Fragmentation and Transactional Care

The U.S. health system is structurally fragmented. Payers, policymakers, innovators, and provider systems have distinct financial incentives. Care cannot stop for wholesale redesign; it is needed 24/7. However, fragmentation becomes costly when these sectors operate without a shared guiding principle.

Care is too often delivered in isolated, transactional steps rather than as an interconnected journey:

- Medicare beneficiaries with multiple chronic conditions see between 4 and 14 different physicians annually, depending on the number of conditions, highlighting the coordination challenges in managing complex care (Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2007).

- People with diabetes and untreated depression are two to three times more likely to be hospitalized, yet only 15% receive behavioral health support (CDC).

- Hypertension patients who participate in integrated medication and lifestyle programs cut their stroke risk by 25%, but fewer than 30% are referred to such programs (American Heart Association).

These failures are not caused by a lack of expertise or technology; they are caused by misaligned decision-making. The system treats a person’s conditions piecemeal rather than considering how those conditions interact, and it rarely funds preventive or behavioral interventions that would improve outcomes. It is not structured to prioritize how emotional well-being influences adherence and lifestyle shifts.

The Cost of Misaligned Priorities

When decisions are not anchored to improving healthy lives, the costs ripple through the system. The Camden Coalition’s work with high-cost “super-utilizers” demonstrates the positive impact: 5% of patients account for nearly 50% of U.S. healthcare spending, mainly driven by preventable emergency visits and hospitalizations. Camden reduced hospital admissions by 26% within six months by coordinating medical, behavioral and social services.

Other integrated models provide similar evidence:

- Kaiser Permanente’s diabetes care program, which combined weight management, behavioral health, and medication optimization, cut hospitalizations by 15–20%.

- Depression treatment that combined therapy with medication was 60% more effective than medication alone, yet therapy coverage remains inconsistent.

- Preventive cardiology research led by Valentin Fuster, MD, chief physician officer at Mount Sinai, confirms that 80% of cardiovascular disease is preventable with consistent access to lifestyle, behavioral, environmental and medical interventions.

Even modest shifts in decision-making toward coordinated care could produce significant gains in health outcomes and financial sustainability.

Decades of scientific and technological advances have been insufficient to counter the U.S. obesity crisis, which continues to grow, affecting more than 40% of adults and nearly 1 in 10 with severe obesity (CDC). Rates approach 50% among Black and Latino adults, yet fewer than 2% of eligible patients receive anti-obesity medications — a clear sign the system is not equipped for sustainable intervention. Most primary care physicians lack time, training, or coverage support, leaving patients without consistent access to effective treatment.

Patient-centered pathfinders like FlyteHealth are emerging to close this gap. They offer personalized, evidence-based care models that combine expert specialty care to address the metabolic domino effect of obesity on high blood pressure, diabetes, and mental health. Yet, few obesity medical specialists are trained to address this epidemic.

Centering Decisions on One Shared Goal

The U.S. cannot dismantle or “reset” its health system — medicine operates continuously, every second of every day. Financial incentives will never perfectly align across sectors. But decisions — whether by payers, policymakers, innovators, or provider systems — can be oriented around a single, unifying goal: improving people’s physical and mental health.

- Payers can invest in interventions that reduce downstream costs, such as funding behavioral health services for diabetes patients or covering community-based lifestyle programs for hypertension.

- Policymakers can prioritize outcome-based reimbursement pilots, building on successful models such as Camden’s hot-spotting approach or the Medicare Diabetes Prevention Program. They can consider what care people on Medicaid will lose and the impact on community health facilities.

- Product innovators can design solutions that connect care rather than create new silos, emphasizing interoperability and whole-patient monitoring. They can revisit how patient assistance programs can be easier to navigate and if direct-to-consumer efforts can elevate disease awareness and access to care programs.

- Provider systems can expand the roles of care navigators or “quarterbacks” who help patients manage multiple conditions — a strategy that has been shown to improve adherence and reduce emergency visits.

Michael Rosenblatt, MD, Prix Galien Committee Chair, a senior advisor to private equity firm Flagship Pioneering, former Chief Medical Officer of Merck, and former Dean of Tufts University School of Medicine, whose career has traversed drug development, hospital-system leadership, medical school dean, and advisor to private equity focusing on health innovation, summarizes the stakes: “Innovation has to extend beyond the molecule to how care is delivered. Otherwise, the most remarkable science will never reach its potential.”

Trust and Relationships: The Connective Tissue

Evidence suggests that when patients feel known and supported, outcomes improve. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation found that patients who trust their care team are 50% more likely to follow treatment plans. A Patient Education and Counseling meta-analysis showed that physicians rated highest in understanding and connection achieved 40% lower treatment non-adherence in chronic conditions. For people with diabetes, that trust translated to an average 0.5% reduction in HbA1c levels — a significant difference in long-term complication risk.

Communications as a Catalyst

For advocacy, policy, and industry communications professionals, shaping the conversation around this shared goal is critical. Facts alone are not enough; they resonate when linked to human experience.

Stories should highlight how prioritizing whole-person health changes outcomes:

- A woman with high blood pressure avoided a second stroke because her insurer funded a community fitness program.

- A young adult with diabetes and depression whose condition stabilized when therapy and nutritional counseling were finally covered.

- A patient community worked alongside a drug development team to develop clinical trial inclusion criteria so that people from remote communities could participate and benefit from expert care.

Data anchors those stories in reality:

- 26% fewer hospital admissions in Camden with coordinated care.

- 15–20% reduction in diabetes hospitalizations with integrated weight management.

- 15% weight loss through coordinated obesity care programs combining medication, nutrition, and behavioral support.

- 60% greater effectiveness when depression is treated with both therapy and medication.

Using consistent language — “health lives,” “whole-person outcomes,” “value through coordination” — can help unify stakeholders and reframe discussions away from defending silos to asking a single question: Does this decision improve people’s health lives?

A Practical Path Forward

The United States does not need to spend more, dismantle its system, or wait for perfect alignment of financial incentives to begin improving outcomes. It requires a clear, shared north star for decision-making: improving people’s physical and mental well-being.

The evidence is already clear. When systems — however fragmented — make decisions prioritizing healthy lives, emergency visits decline, chronic conditions stabilize, and quality of life improves. The paradox of abundance without outcomes will not be solved by more spending or more technology alone. It will be solved when every decision, from coverage policies to clinical design to innovation investments, is measured by a simple standard: Will this help people live healthier, longer, better lives?

That is not aspirational — it is achievable. The proof is already in front of us. Perhaps the real solution is to stop lamenting what is broken and start collaborating on what works.

This was originally published in Being Well Health and Wellness, A Medika Life Publication and is syndicated here with permission.