By Elizabeth H. Bradley, Amanda Brewster and Leslie Curry

By Elizabeth H. Bradley, Amanda Brewster and Leslie Curry

Twitter: @commonwealthfnd

Many people, particularly older patients, are readmitted soon after being discharged from the hospital. These unexpected return visits are expensive and challenging for patients and their families, and costly for Medicare. Nearly 20 percent of Medicare beneficiaries experience an unplanned hospital readmission, with an estimated cost to the American public of about $26 billion per year. Avoiding or at least reducing unplanned readmissions is a national priority; however, readmission is a complicated process and not easy to predict or prevent. With support from The Commonwealth Fund, our research team at the Yale School of Public Health undertook a study between 2010 and 2015 to understand how this might be accomplished.

What Did We Learn About National Efforts to Reduce Rehospitalizations?

Hospitals that participated in national efforts to reduce readmissions, including the State Action on Avoidable Rehospitalizations (STAAR) and Hospital-to-Home (H2H) initiatives, reported that these efforts motivated them to focus on the problem of readmissions, experiment with various strategies to fix it, and learn from one another. Active from 2009 to 2013, the STAAR initiative focused on hospitals in Massachusetts, Michigan, and Washington. STAAR encouraged collaboration across organizational boundaries and focused on enhancing assessment of posthospital needs, patient education, handoff communications, and timely follow-up. H2H was a national effort which ran from 2009 to 2012 and emphasized early follow-up, postdischarge medication management, and patient education. Using surveys and interviews with clinical and administrative staff, we sought to understand which strategies were most effective in reducing unplanned readmissions, and how hospitals turned new strategies into routine practices.

What Strategies Worked?

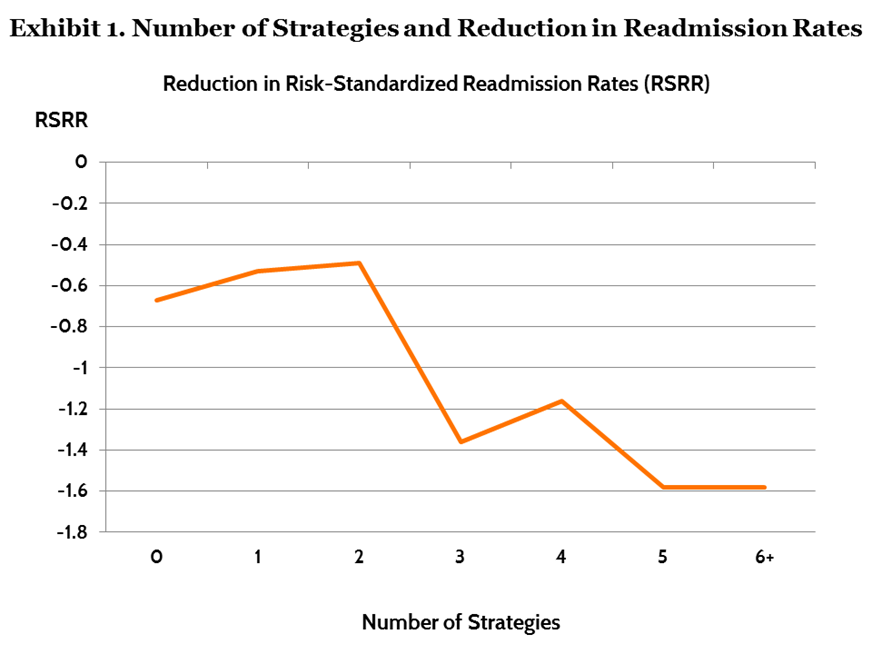

We surveyed 478 hospitals participating in either STAAR or H2H in 2011 and then again in 2012 to understand which strategies each hospital had introduced and whether and how their risk-standardized readmissions rates had changed. Only one strategy was consistently associated with reductions in risk-standardized readmission rates: discharging patients with their follow-up appointments already made, which was associated with a 0.63 percentage point reduction in readmission rates. No other single strategy proved significant, however. Yet, hospitals that implemented three or more different strategies had significantly greater reductions in risk-standardized readmission rates than hospitals that implemented less than three strategies (Exhibit 1). Reductions of 1.29 percentage points were average among the 117 hospitals that adopted three or more new strategies. And these hospitals used 93 unique combinations of strategies to achieve reductions—suggesting there’s no magic bullet to avoiding readmissions. Although introducing three or more strategies compared with fewer strategies was associated with lower rates of unplanned risk-standardized readmission, adding four, five, or six strategies was not associated with significantly more benefit than was attained for those hospitals that implemented three strategies.

What Makes New Strategies Become Routine Practices?

What Makes New Strategies Become Routine Practices?

Our research suggests that successful integration of new strategies requires more than good ideas. Keeping new strategies in place often depended on key staff shepherding the changes for up to one year—until long-term mechanisms were in place to support them. There appeared to be three pathways through which strategies became routine:

- Intrinsic rewards (the innovations either made staff’s jobs easier or more fulfilling);

- External incentives, such as financial bonuses for complex task shifts, or

- Automation, such as ordering systems for more simple tasks.

The way that a new strategy transformed into a routine practice depended on the nature of the rewards and complexity of the tasks involved.

Finding the Right Mix of Tailored Strategies

Hospital readmission rates result from the confluence of diverse patient, provider, and organizational factors. Despite a wide range of hospitals and five years of study, we found little evidence that specific strategies conferred improvements across hospitals, aside from booking follow-up appointments before discharge. Rather, adopting at least three strategies, tailoring implementation efforts to local circumstances, and persistence over time seemed to be keys to success.

Despite this complexity, the U.S. saw measurable reductions in readmissions rates while the two national efforts were active. The national risk-standardized readmission rate for heart failure, for example, fell from 23.4 percent to 21.9 percent during this period. Although neither campaign provided a simple recipe for reducing readmissions, our qualitative data indicated that convening hospitals around a common agenda and providing a forum to learn from each other helped hospitals jump-start their action on this complex patient-care issue. As with any intervention taking place in the real world, it is difficult to know whether to attribute the improved readmissions rates to STAAR and H2H—or to other changes in the environment, such as public reporting and financial penalties for readmissions for certain conditions initiated by Medicare in 2012. Improvements in readmissions rates likely resulted from several factors, including Medicare’s new policy, increased awareness of readmissions as a problem, and hospital quality improvements sparked by these national initiatives.

This article was originally published on The Commonwealth Fund Blog and is republished here with permission.