By Ashish Jha

By Ashish Jha

Twitter: @ashishkjha

Reducing Hospital Use

Because hospitals are expensive and often cause harm, there has been a big focus on reducing hospital use. This focus has been the underpinning for numerous policy interventions, most notable of which is the Affordable Care Act’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP), which penalizes hospitals for higher than expected readmission rates. The motivation behind HRRP is simple: the readmission rate, the proportion of discharged patients who return to the hospital within 30 days, had been more or less flat for years and reducing this rate would save money and potentially improve care. So it was big news when, as the HRRP penalties kicked in, government officials started reporting that the national readmission rate for Medicare patients was declining.

Rising Use of Observation Status

But during this time, another phenomenon was coming into focus: increasing use of observation status. When a patient needs hospital services, there are two options: that patient can be admitted for inpatient care or can be “admitted to observation”. When patients are “admitted to observation” they essentially still get inpatient care, but technically, they are outpatients. For a variety of reasons, we’ve seen a decline in patients admitted to “inpatient” status and a rise in those going to observation status. These two phenomena – a drop in readmissions and an increase in observation – seemed related.

I – and others – spoke publicly about our concerns that the drop in readmissions was being driven by increasing observation admissions. An analysis by David Himmelstein and Steffie Woolhandler in the Health Affairs blog suggested that most of the drop in readmissions could be accounted for both by increases in observation status and by increases in returns to the emergency department that did not lead to readmission. Two months later, a piece by Claire Noel-Miller and Keith Lund, also in the Health Affairs blog, found that the hospitals with the biggest drop in readmissions appeared to have big increases in their use of observation status. It seemed like much of the drop in readmissions was about reclassifying people as “observation” and administratively lowering readmissions without changing care.

New Data

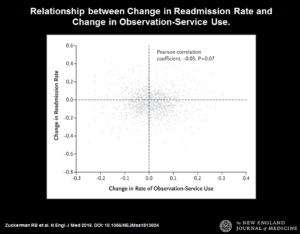

Now comes a terrific, high quality study in the New England Journal of Medicine that takes this topic head on. The authors examine directly whether the hospitals that lowered their readmission rates were the same ones that increased their observation status – and find no correlation. None. If you’re ever looking for a scatter plot of two variables that are completely uncorrelated, look no further than Figure 3 of the paper. The best reading of the evidence prior to the study did not turn out to be the truth. It reminds me of the period we were all convinced, based on excellent observational data, that hormone replacement therapy was lifesaving for women with cardiovascular disease. And that became the standard of care – until someone conducted a randomized trial, and found that HRT provided little benefit to these patients. That’s why we do research – it moves our knowledge forward.

So where does this leave us? Is the ACA’s readmissions policy a home run? Here’s what we know: the HRRP has, most likely (we have no controls) led to fewer patients being readmitted to the hospital. Second, the HRRP does not seem responsible for the increase in observation stays.

Here’s what we don’t know: is a drop in readmissions a good thing for patients? It may seem obvious that it is but if you think about it, you realize that readmission rate is a utilization measure, not a patient outcome. It’s a measure of how often patients use inpatient services within 30 days of discharge. Utilization measures, unto themselves, don’t tell you whether care is good or bad. So the real question is — has the HRRP improved the underlying quality of care? It might be that we have improved on care coordination, communications between hospitals and primary care providers, and ensuring good follow-up. That likely happened in some places. Alternatively, it might be that we have just made it much harder for that older, frail woman with heart failure sitting in the emergency room to get admitted if she was discharged in the last 30 days. That too has likely happened in some places. But how much of it is the former versus the latter? Until we can answer that question, we won’t know whether care is better or not.

Beyond understanding why readmissions have fallen, we also don’t know how HRRP has affected the other things that hospitals ought to focus on, such as mortality and infection rates. If your parent was admitted to the hospital with pneumonia, what would be your top priority? Most people would say that they would like their parent not to die. The second might be to avoid serious complications like a healthcare associated infection or a fall that leads to a hip fracture. Another might be to be treated with dignity and respect. Yes, avoiding being readmitted would be nice – but for me at least, it pales in comparison to avoiding death and disability. We know little about the potential spillover effects of the readmission penalties on the things that matter the most.

So here we are – a good news study that says readmissions are down because fewer people are being readmitted to the hospital, not because people are being admitted to observation status. That’s important. But the real challenge is in figuring out whether patients are better off. Are they more likely to be alive after hospitalization? Do they have fewer functional limitations? Less pain and suffering? Until we answer those questions, it’ll be hard to know whether this policy is making the kind of difference we want. And that’s the point of science – using data to answer those questions. Because we all can have our opinions – but ultimately, it’s the data that counts.

About the Author: Dr. Ashish K. Jha is a practicing Internist physician and a health policy researcher at the Harvard School of Public Health. This article was originally published on his blog, An Ounce of Evidence.