By Sarianne Gruber

By Sarianne Gruber

Twitter: @subtleimpact

ProPublica, a New York City based non-profit newsroom, focuses on stories as they describe have a “moral force”. Last month, Olga Pierce and Marshall Allen, reporters who cover health care and patient safety issues, released to the public the Surgeon Scorecard. The database is searchable by location and state, by hospital and by surgeon for a selected procedure, which drills down to each surgeon’s performance. Patients considering an elective surgery on any of these eight elective procedures: knee replacement, hip replacement, gallbladder removal (laparoscopic), lumbar spinal fusion posterior column, lumbar spinal fusion anterior column, prostate resection, prostate removal or cervical (neck) spinal fusion, can use this new searchable online database to find out how surgeons and hospitals across the nation perform based on complication rates. ProPublica’s objective is to give the public access to information that they would have not known prior to selecting a surgeon, simply adding transparency with assessable data. As patient safety activists and journalists, concern and curiosity as to why recent statistics show that between 210,000 and 440,000 patients a year die from medical errors, led them to delve into data for answers. ProPublica discovered that even selecting a “good” hospital there is variation in outcomes by surgeon. Their analysis showed 50% of all hospitals in America have both high and low performing surgeons.

The data for the Surgeon Scorecard was provided by the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Service (CMS). ProPublica received Medicare billing data (a 100% Standard Analytic File) for 5 year period from 2009 to 2013. As required by CMS, identities had to be concealed for all 63,173 patients, who readmitted during 30 days post op with a complication, or the 3,405 patients who had died. A total of 2.3 million procedures including hip and knee replacements, three types of spinal fusion, gallbladder removals, prostate removals and prostate resections were analyzed. To further protect privacy, CMS restricted the reporting any number of complications from 1 to 10, or data which could be used to calculate a number within that range. The Surgeon Scorecard reports adjusted complication rates for 16,827 surgeons operating at 3,575 hospitals. And as a precaution, no rate was reported if a surgeon performed an operation fewer than 20 times.

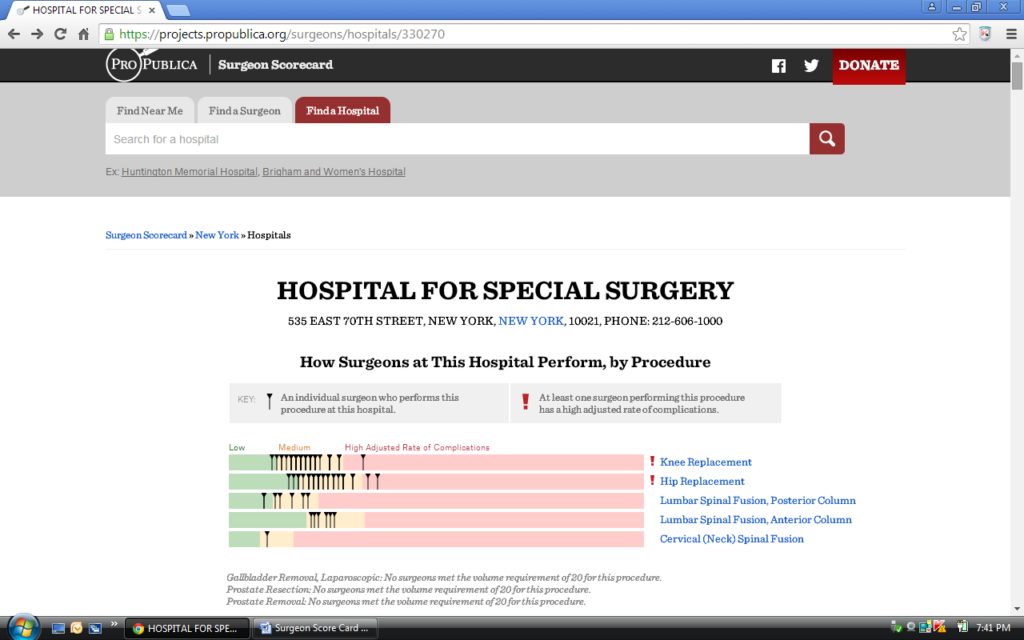

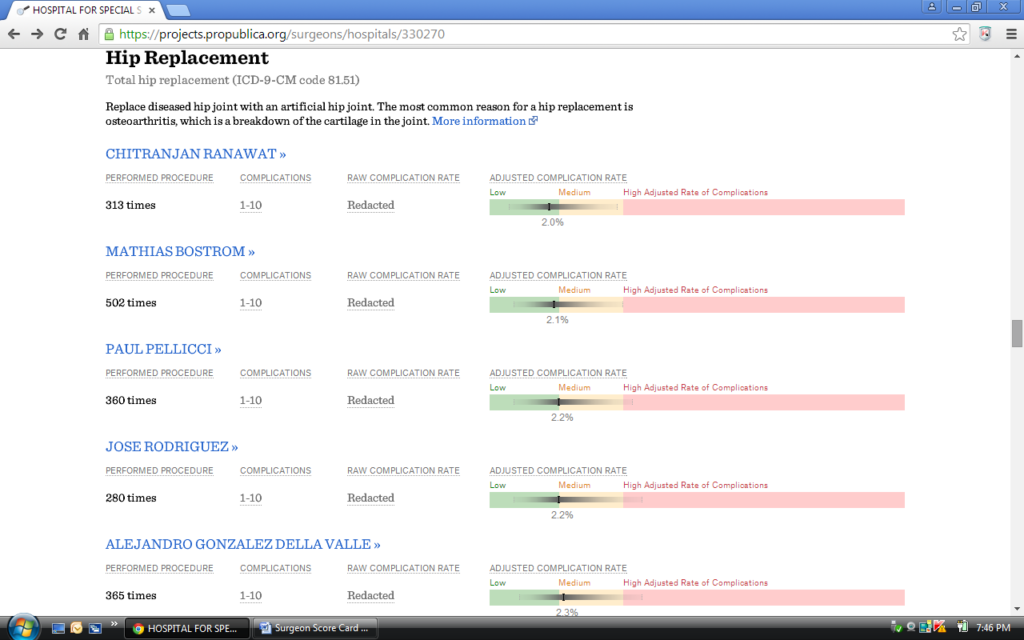

Presented in Figures 1 and 2 are samples of the data visualizations and statistics made available by Surgeon Scorecard search.

Figure 1. Scorecard Screen Shot of Surgeon Performance for the Hospital of Special Surgery in New York, NY

Figure 2. Scorecard Screen Shot of Hip Replacement by Surgeon for the Hospital of Special Surgery in New York, NY

Concerns: The Scorecard Critique

A discussion of the methodology is provided with the scorecard. Exclusions are noted. Physician assessment of complications mentioned. Rules established for counting the 30 day readmissions. Raw rates and adjusted complication rate rules (plus a technical whitepaper on the model and appendices). Data limitations due to having patients enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare only. Medicare data does not include hospital stays paid for by private insurance or other government programs such as Medicaid. And as a result many cases that could move a surgeon’s complication rates up or down are not counted. There was acknowledgement that “harm to patients can be a relatively rare event”, therefore difficult to model. The main metric used for surgeon and hospital comparison is the Adjusted Complication Rate, which is calculated by applying the modeled surgeon random effect to the entire patient population for a procedure in the analysis.

Upon release of the Surgeon Scorecard, there has been much debate. Statements have been made on (but not limited to) on the following topics:

- Paucity of data

- Data quality, completeness and accuracy

- Using Medicare data only (patient age >65)

- Exclusion of outpatient Medicare cases, ER admissions and private health insurance

- Limitations of billing data, no case-specific or chart review

- Statistical Methodology, Random-Effects Models, Use of Confidence Intervals, Simpson’s Paradox

- Health Score with respect to sicker patients

- Presentation and graphic display of the data is misleading.

Yet, despite the observed shortcomings, the popular consensus for the huge undertaking by Allen and Pierce is that we have a starting point. And in support of transparency of information and patient engagement, work should and must continue. Dr. Edward J. Schloss, Medical Director, Cardiac Electrophysiology, at The Christ Hospital, Cincinnati Ohio in An Open letter to Healthcare Outcomes Researchers, Journalists and Data Scientists, is requesting an expert peer review to commence. In his letter states, “This analysis was a great idea, but if fails to deliver on its goals. The data and methodology both have significant flaws. I say that from the perspective of a working clinician and clinical researcher with over 20 years experience, but I’d like to see a higher level of review. This project is as much science as it is journalism. Surgeon Scorecard should be peer reviewed and critically discussed as would any scientific outcomes study”. At the conclusion of the letter, Dr. Schloss says “ProPublica has invited expert commentary by email at scorecard@ProPublics.org. Please submit your comments there, and leave me a copy in the comments section of this post”.

Several physicians, statisticians and journalists wrote their views on the Surgeon Scorecard. Their comments and insights are worth reading. Noted below are the authors and their article.

- Christos Argyropoulos , MD, The Little Mixed Model That Could But Shouldn’t Be Used To Score Surgical Performance. Statistical Reflections of a Medical Doctor. Jul 30, 2015.

- Benjamin Davies, MD, ProPublica’s Surgeon Score Card: Clickbait? Or Serious Data? Forbes. Jul 14, 2015.Christina Farr, What You Need to Know About the New Surgeon Scorecard App. Future of You. KQED. Jul 16, 2015.

- Andrew Gelman, PhD, Pro Publica’s New Surgeon Scorecards. Statistical Modeling, Casual Inference, and Social Science. Aug 4, 2015.

- Ewen Harrison, MD, The Problem with ProPublica’s Surgeon Scorecards. DataSurg. Jul 15, 2015.

- Saurabh Jha, MD, When a Bad Surgeon is the One You Want: ProPublica Introduces a Paradox. KevinMD. Jul 23, 2015.

- Robert Lowes, Online Scorecard Shows Surgeons’ Complication Rates. Medscape. Jul 15, 2015.

- Jon Mandrola, MD, Failing Grade for ProPublica’s Surgeon Scorecard.Medscape. Jul 23, 2015.

- Naseem Miller, Scorecard Ranks Surgeons on Elective Procedures. Orlando Sentinel. Aug 5, 2015

- Jeffrey Parks, MD, Why the Surgeon Scorecard is a Journalistic Low Point for ProPublica. KevinMD. Jul 22, 2015.

- Scott Stump, ’Surgeon Scorecard Aims to Help You Find Doctors Lowest Complication Rates’. Today NBC Broadcast Jul 20, 2015.